What My Dad Taught Me About Work

My dad turns 70 today. Here's what I learned from watching him on the job.

Shortly after my dad turned 15, his father sat him down in their garage in Detroit, Michigan and got real with him.

“I don't have the money to pay for college,” my grandfather, a line worker at the local General Motors plant, told my dad. “If you want to go, you're going to have to find a way to pay for it yourself.”

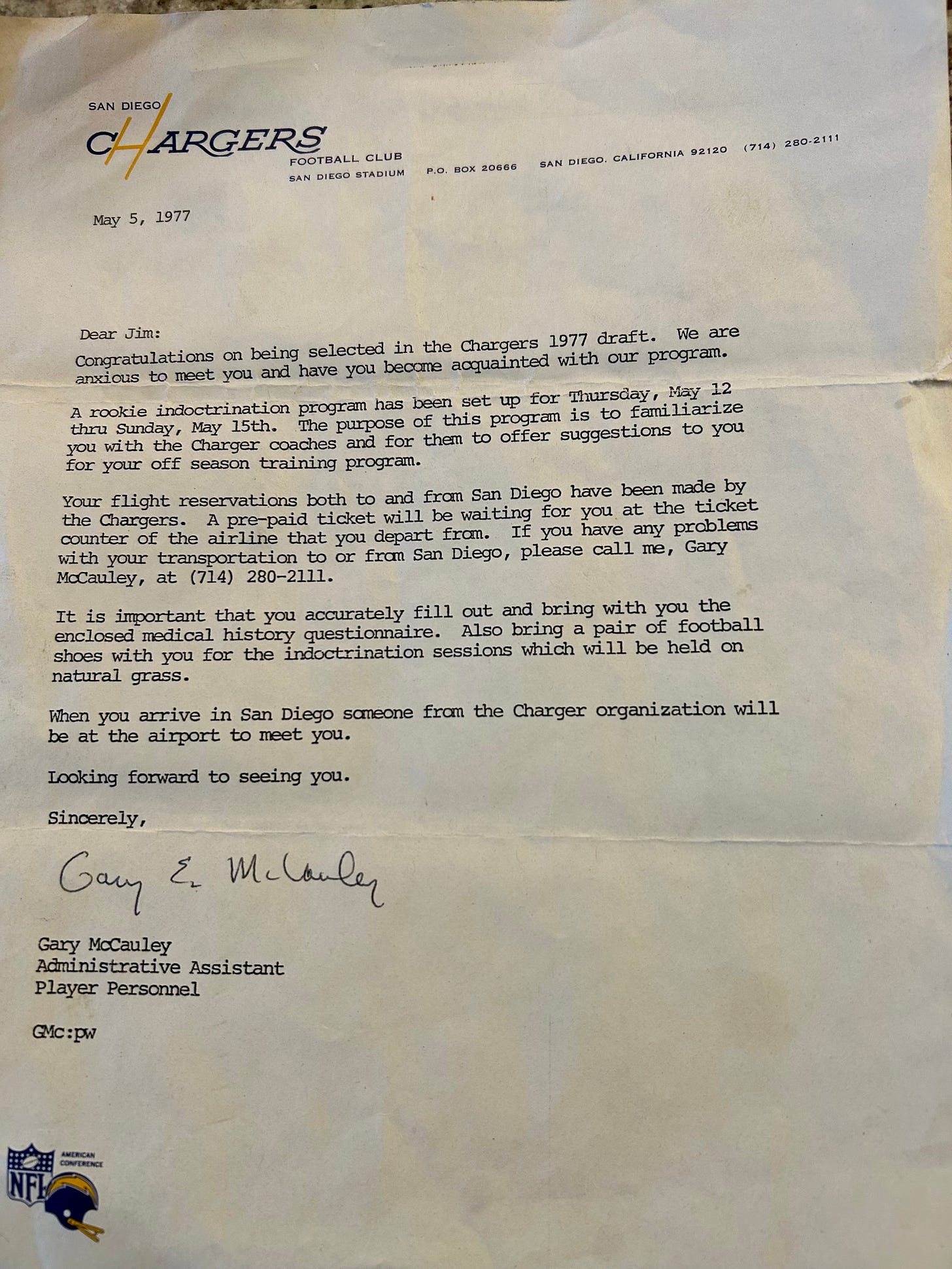

That’s a heavy load to shoulder when you’re barely a teenager. But my dad found a way. A few years later, he landed a full-ride scholarship to play football at Eastern Michigan University. After playing all four years, he was selected in the 12th round of the NFL draft by the San Diego Chargers. But his professional football career was to be short-lived. Soon after, he was traded to the Miami Dolphins, and then cut from the roster before the regular season kicked off.

With football behind him and a criminal justice degree in hand, he pivoted to law enforcement. Fast-forward eight years later, and he had risen fast inside the Washtenaw County Sheriff's Department: from patrolman, to motorcycle cop, to detective, to SWAT team member, to captain of the SWAT team.

Then, in 1985, I showed up. And around that time (knowing more kids were likely on the way), my mom politely implored him to consider a career that didn't require kicking down doors while holding a 12-gauge shotgun.

Dad started looking around. And eventually, through an ex-Sheriff's Department colleague, he got an offer from a family-owned company called Domino's Pizza to head up corporate security. He initially turned it down. He loved being a police officer, and had mixed feelings about joining the business world. But with a young family to provide for, a quiet ambitious instinct urging him to do more with his career, and an impassioned sales pitch from his former teammate, he took the job.

That decision changed everything: for him, for our family, and for how I do my work.

What started as a security gig soon led to a promotion to operations management. And then, shortly after Bain Capital bought Domino's in 1998, the company’s new CEO, David Brandon, made my dad his special assistant, deputizing him as his source of ground truth about the business. Dave gave my father a simple but critical mandate: Maintain the health of Domino’s franchisee base, and solve the little problems before they become big ones.

He spent the next twenty years doing that job. Through a successful PE investment, through an IPO, and through three CEO transitions.

I got to watch the whole thing.

It taught me a lot.

Today, my dad turns 70. And on his birthday, I want to share three important lessons I learned from watching him do his job.

Lesson 1: Pick Up The Phone

I spent a lot of my time as a kid in the passenger seat of my dad's black Chevy Suburban. He insisted on driving us to every sporting event he could (and all three of us Stansik kids played a lot of sports growing up). The only catch to his chauffeur service was he liked to talk on the phone.

This was the era of the early cell phone. As far back as I can remember, my dad had one of those big brick phones with him, and when he spoke into it, his booming baritone voice would fill the entire cabin of the car. He'd mostly take calls from franchisees. And as we drove to whatever practice or tournament was that day, I'd sit there listening to his side of these conversations.

You couldn’t not listen.

I remember that he asked a lot of questions. Real questions. The kind that came from genuine curiosity, not from some predetermined agenda.

Then he'd go quiet. I remember long pauses, the phone held to his ear, watching my dad just listen. I could hear voices coming through the phone - sometimes frustrated, sometimes excited, sometimes confused. He'd always let them finish. Then he'd ask another question.

I didn't realize it then, but I was watching someone who understood that business is fundamentally about engineering agreements between people. And agreements don't happen without talk and listening to each other. They don't happen through email chains or workflow automation or e-signature platforms. They happen when humans connect, and over time, knit together a foundation of mutual trust they can use to make hard decisions together.

As an operating partner, I spend most of my time trying to create agreements that improve our businesses. I can spot operational gaps and build frameworks all day long, but nothing useful actually happens from those diagnoses without buy-in from the people who manage our companies. As I’ve written before, part of my job is to be a kind of strategic diplomat. Sure, I have to diagnose problems and opportunities. But more importantly, I have to get people on the same page about what to do about them.

That second part is the more important, and more challenging, part of the job.

When I'm feeling stuck, when the vibe is off, or when I'm clearly not on the same page as one of our CEOs… that's when I remember those car rides with my dad. That's when I know I need to pick up the phone. That’s when I know I have to have a conversation. And that’s when I trust that adding a dose of human connection to whatever we're working on will create some kind of goodness: revealing new options, building more buy-in, or, at the very least, sending a quiet but critical signal: I care about you, and I care about us figuring out a way to make the most of this situation together.

My dad understands the value of human connection at a deep, intuitive level. He knows that every business problem was really a people problem. And people problems get solved by talking to each other.

So when in doubt, I pick up the phone.

Just like him.

Lesson 2: Have a Standard

At my dad's retirement party, the Domino's corporate communications department unveiled a tribute video they had made for him. In the opening scene of that video, Stan Gage, one of my dad’s teammates on the Domino’s leadership team, sits at a desk and holds up a piece of weathered paper. On the paper is a hand-typed copy of a speech Stan heard my dad give twenty years earlier.

In that speech, my dad outlined his standards for how the Domino’s leadership team should treat its franchisees. Standards like:

Know your franchisees. Know what motivates them.

When you talk, you can’t hear what’s going on.

The best way to build a relationship is to ask someone for their advice.

Ask your franchisees what’s driving them crazy, and work to fix those things.

Share best practices. It’s one of the best tools you have at your disposal.

Occasionally meet without an agenda.

Know the contract.

Those standards seem simple. They are simple. But my dad was relentless about reinforcing them. Once he decided on a standard, you better believe that people knew about it.

Here's a small example: In the early days of email, when my dad would send trip reports or follow-ups from strategy discussions, he always capitalized the word "FRANCHISEE." In every message, every time. He wanted to put special emphasis on that word. He wanted people to think about that word as if it were the atomic unit of growth for the company. And he wanted the executive team at Domino’s to remember that they worked for the franchisees.

I carry this idea with me everyday. A big part of being an operating partner is paying attention to standards. What are the universally-applicable principles we should hold our companies to, and how do we help our companies internalize them and translate them into their handwriting? When our team at ParkerGale is at our best, we spend our time teaching simple, time-tested standards to our companies, helping to make them stick, and then measuring whether they're working so we can make adjustments. And guess what? Writing those standards down and creating a shared language around those standards is how you make them stick. Though his list of standards uses simple language, my dad understood the power of writing them down and reinforcing them. It works.

I also use this principle when hiring . I've often said that the best test of whether someone will be a great hire is based on whether they have two qualities: high standards and the means to detect if they're being met. Pretty much everything I ask in interviews (from CEO on down) is designed to assess for those qualities.

Qualities my dad embodied, wrote down, and reinforced.

Qualities people still remember him for.

Lesson 3: Get On The Plane

My dad flew a lot during his time at Domino's: At least a couple million miles the last time I checked. He was on the road three-ish days a week most weeks, and I think he relished his role as the guy who was out in the field as the company’s eyes and ears.

As part of his work with the franchisee base in the 2000s, my dad had to help lobby for a larger national advertising budget. The company needed to convince their franchisees to give up some short-term profits so Domino's could allocate more money to more expensive marketing programs with broader reach. There was real skepticism on the ground. The work wasn’t unlike what a legislator has to do to get a bill passed - lots of handshaking, listening to concerns, and some horse-trading. My dad was basically trying to pass a resolution that takes resources away now for the promise of a long-term return. That’s always a hard deal to get done, but my dad's relationships with the franchisees helped the company pull it off.

What followed is now one of the most famous marketing pivots in modern corporate history. In December 2009, Domino’s launched the “Oh Yes We Did” campaign, a risky, brutally honest effort where the company admitted its old pizza wasn’t good enough and announced a completely re-engineered recipe. A few months later, in April 2010, they doubled down with national ads showing skeptical “pizza holdouts” tasting (and endorsing) the new product on camera. It was a campaign that cost big dollars, drew national headlines for its candor, and successfully reset how people thought about the brand.

The campaign paid off. From 2010 to 2019, the number one performing stock in the S&P 500 was Netflix. Number two? Domino’s Pizza.

That story, and those results, could never have happened without buy-in and sacrifice from the franchisees. And that buy-in and sacrifice could never have happened without the strength of the relationships and face-to-face time my dad had accumulated with those franchisees. All of it started with human connection.

But, for my dad, getting on the plane wasn't just about lobbying for big strategic initiatives. It was also about showing up when your teammates needed you.

After Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, my dad was one of the first members of the Domino’s team on the ground in New Orleans. He brought with him a duffel bag with $50K in cash inside and one goal: Take care of Domino’s employees.

He stayed up late making and delivering pizzas to first responders, helped franchisees dig their stores out of the rubble, handed out cash to hourly employees, and made sure everyone knew that the company had their back. People still talk about that trip, and what it meant to have someone from the executive team there on the ground, just days after the disaster.

In our family cottage in northern Michigan, there's a framed photo of my dad on the ground in an old-school Domino's polo shirt, walking through the aftermath of the hurricane.

At first glance, it's a scary-looking picture. The landscape is flat and desolate. There are no buildings left standing, and there are piles of debris everywhere. But knowing the backstory, I get a good feeling when I look at that photo. I can guess the way these people felt when someone from their leadership team flew down to see them before the situation was fully contained. “You matter to us,” is what I think his presence communicated. “We have your back.”

I like that my dad was there when times got tough for his team. And I want the people I work with to feel the same way about me.

Maybe someday we'll have to respond to a natural disaster inside our portfolio. I hope we won't. But when times get tough, I try to remember that private equity isn't just about pressure and performance and hitting numbers. It's also about being there when things don’t go well and supporting the people inside our companies in every way we can.

We ask our teams to do hard things. We raise the bar on the companies we buy. And when we do that, I think we owe them the resources and emotional support and encouragement they need to meet that new, higher bar.

It's one of the reasons I travel as much as I do. I want people to feel a certain way about me and about our team at our fund. I want them to feel like:

"You know… those guys aren’t that bad. They’re in this with us. And they really want to help us win."

You can’t send that signal through a telephone line or a computer screen.

You have to get on the plane.

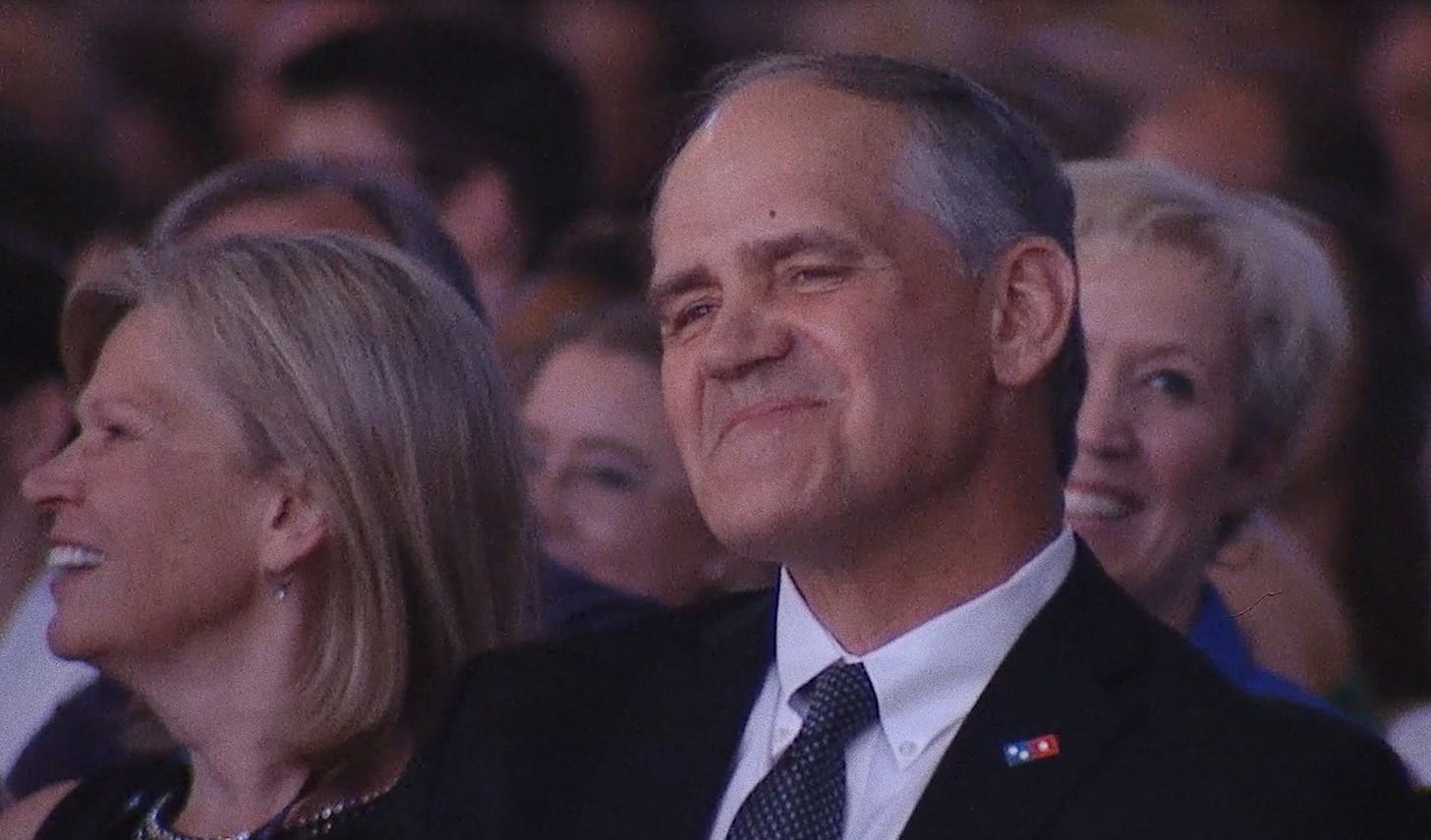

Today, August 29th, is my dad’s birthday. And to mark the occasion, he did something completely unsurprising. He got on his bike and rode his age: 70 miles in a row as he turned 70.

I think it's his way of saying he's still got it. I think it's his way of saying he can still do hard things.

Wharton, Bain, ParkerGale: Each stop in my career has taught me something different. But my most important business lessons have all come from Jim Stansik: a guy who picks up the phone, a guy who lives and works by a set of standards, and a guy who gets on the plane.

A guy who showed me what it means to be a businessman.

I am who I am, and I work how I work, because I am his son.

Happy birthday, Dad.

Thanks for everything you’ve taught me.

Your best post yet. Nice work, Dad.

This is great, Paul. Thanks for sharing your dad's career and insightful and inspiring way of leading his life and business.